James Stirling at 100

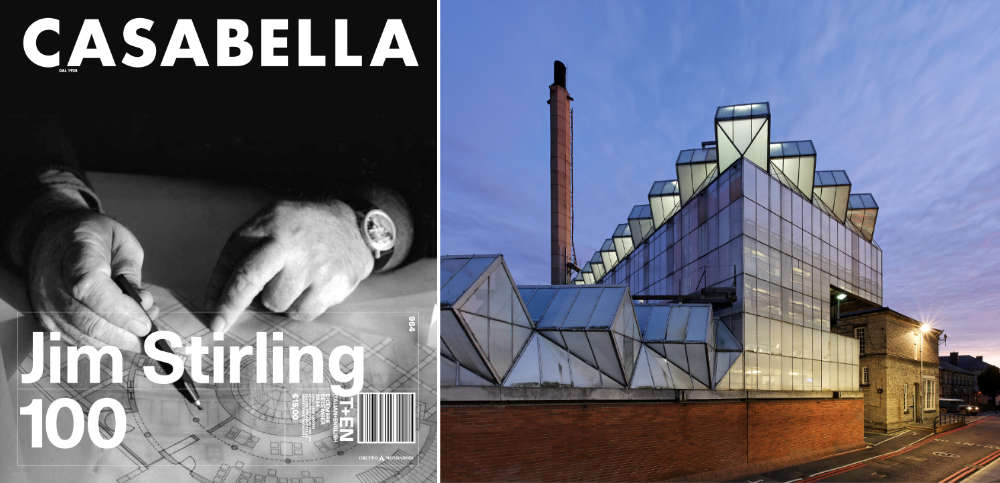

In December 2024, Casabella n. 964 dedicated its entire issue to James Stirling in celebration of his centenary. One of the most inspiring British architects of the 20th century and an alumnus of the University of Liverpool School of Architecture, Stirling was thoroughly analysed in this special issue, curated by Dr. Marco Iuliano as guest editor.

Stirling 1924-2024

Famous for his refined and occasionally biting wit, which permeates both his works and his personality, James Stirling also amused himself by playing with dates, to the point of altering his own date of birth, which was 22nd April 1924, not 1926 as many publications continue to indicate today. The reason for this deception is not known; it was probably just lighthearted jest, perhaps not totally free of advantages.

The issue of Casabella offers an overview of Stirling’s oeuvre, compiled in conjunction with the centenary of his birth. It starts from documents which broadly contributed to the acclaim he earned as one of the leading protagonists of contemporary architecture, alongside some new, as-yet unpublished materials. The materials come from private and public collections: in particular, from the London-based archives of Mark Girouard, the studio of Stirling, Wilford & Associates and Drawing Matter, the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal, and the Archivio Progetti of the IUAV University of Venice.

The issue is organised into four sections. The first one traces a timeline across the most outstanding moments of Stirling’s career, from his training to his travels, from the various locations of his studio to the main exhibitions and publications regarding his work, all the way to the projects, whether implemented or remaining on the drawing board. This “map” forms a critical profile of his figure as an architect, guiding readers through his unusual personal and professional life. The second section analyses two central aspects that can help us to understand Stirling’s remarkable success: the working method, shared over the years, with James Gowan, Michael Wilford, the Associates and the many staffers in his firm, and the use of drawing, a tool for thinking, as an integral, original factor that constituted a true cultural project. The third chapter brings together twelve works of architecture and interprets the concepts of “series” and “one offs” which Stirling assigned to his works. The magazine comes to a close with the reproduction of a letter and the text of a lecture, each belonging to two very different moments in Stirling’s life, and finally an anthology of writings relating to his oeuvre.

Looking back on Stirling enables us to shed light on the timeliness of his work and the importance of his intellectual legacy. This is a heritage that is hard to grasp, but one that resonates even more in the present cliché-ridden vacuum, when architecture seems to be engaged in narcissistic self-reflection while ignoring Stirling’s legacy.

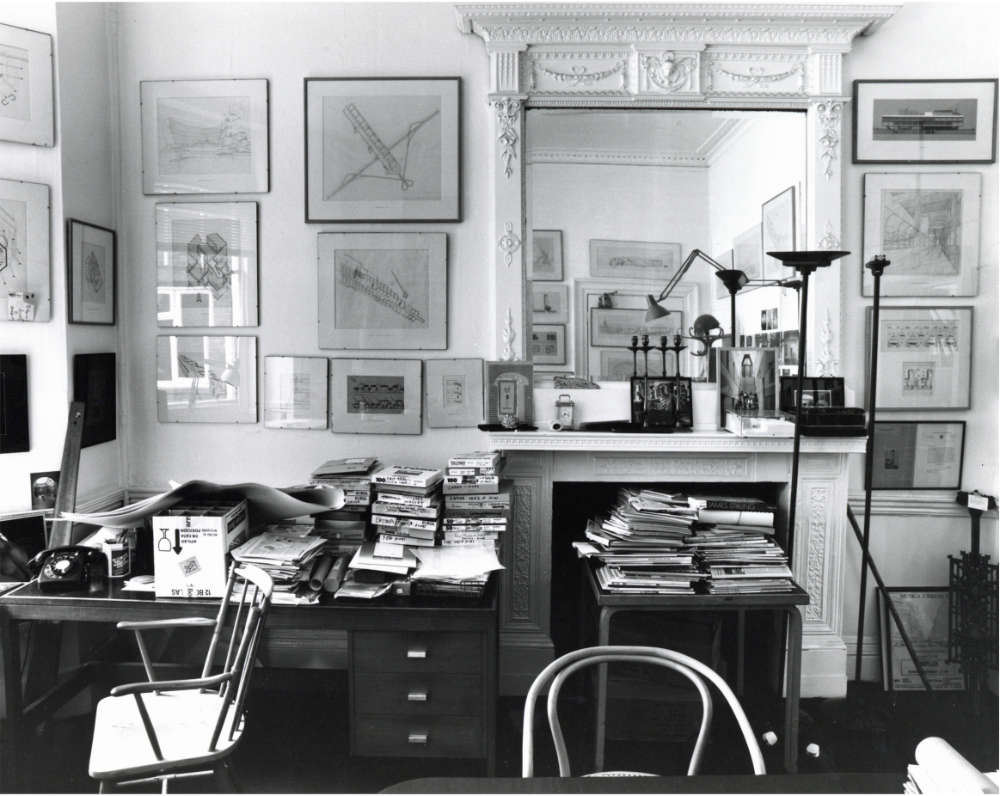

Stirling Wilford and Associates office at Gloucester Place, London (ph. John Donat, 1986; Girouard Archive)

On Stirling’s method

Although James Stirling is known as one of the greatest exponents of architectural culture in the second half of the 1900s, there have been few attempts to describe his working method across the forty years of his career. Architectural historians have analysed many of his works in critical essays, and starting from the reflections of Reyner Banham and Charles Jencks, his output has been seen first as Brutalist, and then as Postmodern. Stirling always rejected such labels, defining the work of his studio simply as “modern,” though without revealing its design process. As his most influential mentor, Colin Rowe, has noted, Stirling was quite determined to keep his architectural and theoretical positions off-limits. Conducting an initial systematic analysis of the archive of Stirling and his partner Michael Wilford, Anthony Vidler has suggested that the wealth of documentation conserved at the Canadian Centre of Architecture in Montreal should be studied case by case to grasp the creative process. Though sharing this position, in the attempt to define the modus operandi of the studio, it may be more useful to retrace the architect’s background, along with the reflections of Stirling and the architects who worked with him over time, in an attempt to identify the method that generated the architectural oeuvre.

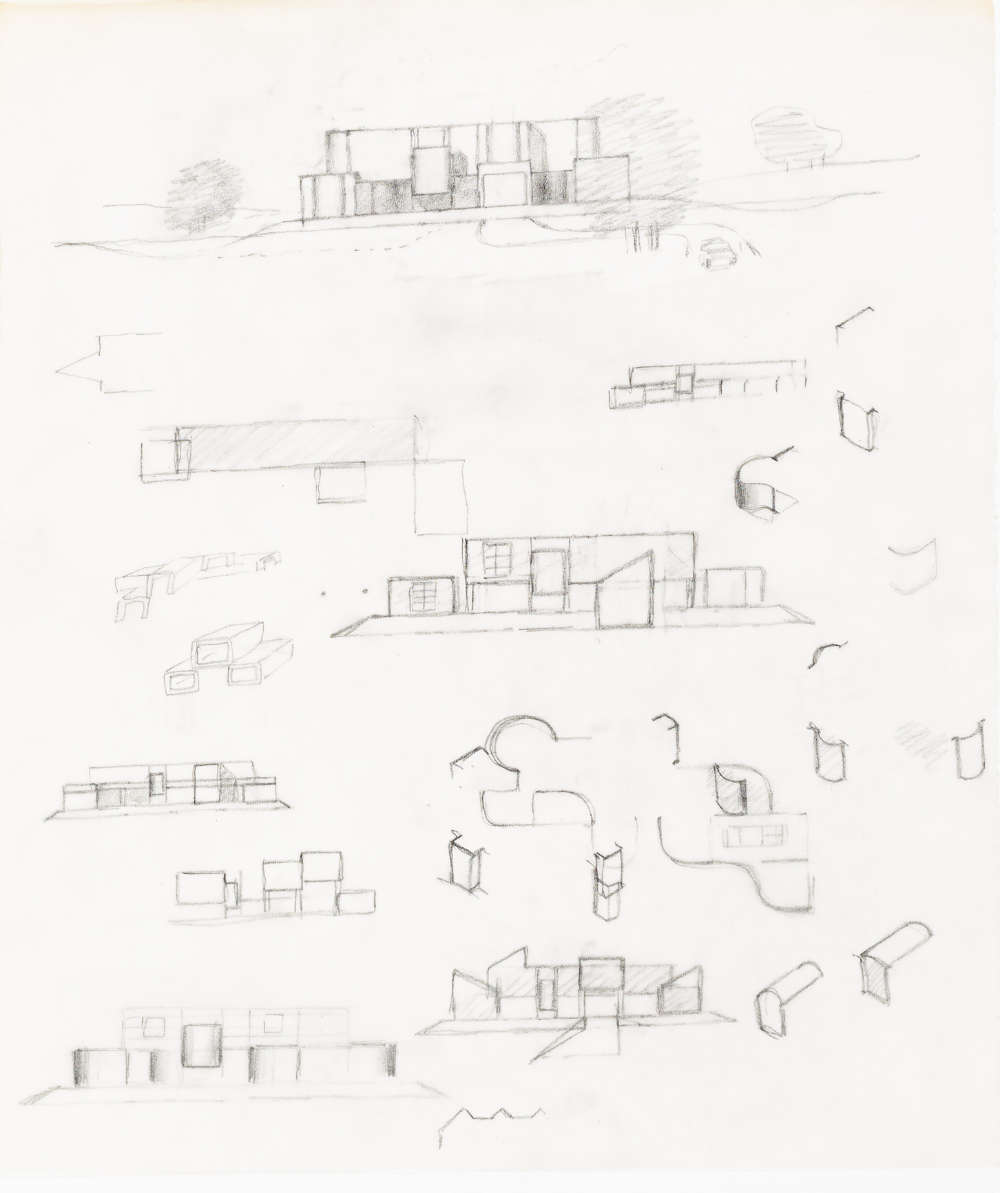

James Stirling, study for a house, appx. 1956 (Drawing Matter)

Stirling acknowledges that “intelligent writing takes me more than designing.” Over the years, he wrote various articles – on the Maisons Jaoul, Ronchamp, and the functional tradition – and he also offered careful descriptions of his projects. Rarely, and only in a partial way, does he describe his work method. In 1975, he published writings in a range of international magazines – including Casabella, in the March issue – referring to the content of a lecture delivered at a congress in Iran the previous year. The title chosen by Architectural Review in May is evocative: “Stirling Connexions.” The text explores the relationship with various historical precedents, juxtaposing a careful selection of buildings from the past with photographs of his projects, suggesting derived forms—almost an architectural version of one of the plates in the figurative atlas of Aby Warburg, Mnemosyne. Fifteen years later, he devoted slightly more than one page to design philosophy in Architectural Design (nn. 5/6, 1990), in a monographic issue accompanied by the usual overview of recent works. Mark Girouard, Stirling’s biographer, through the painstaking interviews conducted with members of the firm, has been able to outline the more operative aspects of the design process. The early period with James Gowan has been covered, during which the ongoing interaction—though lacking a clear dynamic—generated healthy competition, benefiting the variety and quality of the studio’s output, without allowing one of the two characters to prevail over the other. When the partnership came to an end in 1963, Stirling moved from Regent’s Park to Gloucester Place, a second London office that was to house the firm for over 20 years. This passage marked a significant change for Stirling, since the separation from Gowan permitted him to further develop his ideas, without the direct influence of his partner, but with the maturity and experience accumulated during the years of collaboration. As Wilford recalls, initially, it was Stirling who suggested the idea for a project, although over time the approach gradually changed. The firm began to resemble a university workshop more than in the past. Every individual was granted the possibility of proposing ideas, from the student who had just graduated to the most expert of architects. Unlike in a university, where each student completes their proposals with the help of one or several teachers, in this case, the project was a single entity, representing the combination of work by different people. Ulrike Wilke, one of Stirling’s students at Yale University towards the end of the 1970s and active in the studio from 1980, reports that for every commission, the work always began with a functional analysis of the project and the representation of spaces and their potential layout at a scale of 1:500. Once the program had been ‘visualised,’ the work advanced with the so-called ‘clip’—a series of rapid sketches on stapled sheets of A4 paper, in which the possible design proposals were adapted to the site and identified by a name that would sum up the ‘form’ assigned to that particular option. Once the clips had been gathered, Stirling overlaid tracing paper and modified the projects with a few essential strokes, often using a red ballpoint pen; finally, he returned the updated clips to the architects in the studio. Evaluation of all possible options was a distinctive characteristic of the firm, leading to the final definition of the design. The ideas were discarded or incorporated in a succession of solutions. This method was often joined by another, pertaining to university teaching, namely the ‘pin-up review.’ According to Russell Bevington and Laurence Bain, two architects and associates of the studio, multiple members of the staff were called upon to produce project hypotheses that were then subjected to review, hanging on the walls. In this way, the different ideas could be summed up in a single scheme. When the project reached a satisfactory definition in the plan, the work shifted to axonometric variants, still on A4 sheets (A3 if there were problems of scale). In these first phases, the image had to be comprehensible at first glance. Stirling’s method underscores the ability to orchestrate complex thoughts and bring out a single unified idea that was the result of the contributions of many. This is summarised in a remark by Krier when he says that Stirling “works through a team, not just through their hands, but through their minds: whether he likes it or not, this is his true talent.” Wilford also expresses this concept clearly: “That was the whole point of Jim, really, that he was a design magpie. And that's what was wonderful about working with Jim; there was no personal pride, in that sense. He didn't feel that it had got to be his idea. You knew if Jim had turned something down, it wasn't because he hadn't thought of it but because it didn't have validity in his terms. It wouldn’t pass his scrutiny.” Stirling asserted that projects emerge “inevitably” from the analysis of the site, along with a functional interpretation of the work program. He also deemed it necessary to consider aspects of “form” and “style.” As had already happened for many modern architects, he observed that in his case too, there were moments in which the studio produced buildings in series, so much so that it was possible to talk about a sort of “consistency of three,” as in the so-called red trilogy—Leicester, Cambridge, and Oxford. Conversely, there are also episodes where the completed buildings represent isolated experiments, of a unique nature, which were never replicated later.

James Stirling and James Gowan, Leicester Engineering Faculty (ph. Quintin Lake, 2010)

The first part of Stirling’s statements—the idea that the project emerges from analysis of the site and the program—has already been analysed. What now needs to be understood is the more complex aspect of the reasoning, connected with the language of architecture: how are the aspects of “form” and “style” defined? It is not so simple to identify this practice during the partnership with Gowan, but more clues are available in relation to the later phase of the work. Initially, the projects were located above all in green areas or at the edges of the urban context, a tendency that reversed after the end of the 1960s. Stirling saw the oscillation between modernity and tradition as one of the constants in the work of the studio: “Our work has oscillated between the most ‘abstract’ modern (even high-tech), such as the Olivetti training school; and then obviously the ‘representational,’ even traditional, for instance the Rice University School of Architecture. These extremes have been in our work since the beginning, but significantly in recent designs (particularly the Staatsgalerie), these extremes are being counter-balanced and expressed in the same building.” The strategy did not stray far from the principles of locus and genius loci of Aldo Rossi and Christian Norberg-Schulz. Nevertheless, Stirling applied these principles in a pragmatic way, generating a direct connection between the specificity of the place and the architectural project. At the same time, he did not overlook the creative expedients and technical research, which were not necessarily derived from the surrounding context. While members of the staff carried out precise analyses of the site, often accompanied by photographic surveys, in the office, work proceeded on the operative phases described previously, focusing on the technical aspects by re-examining various case studies on tracing paper.

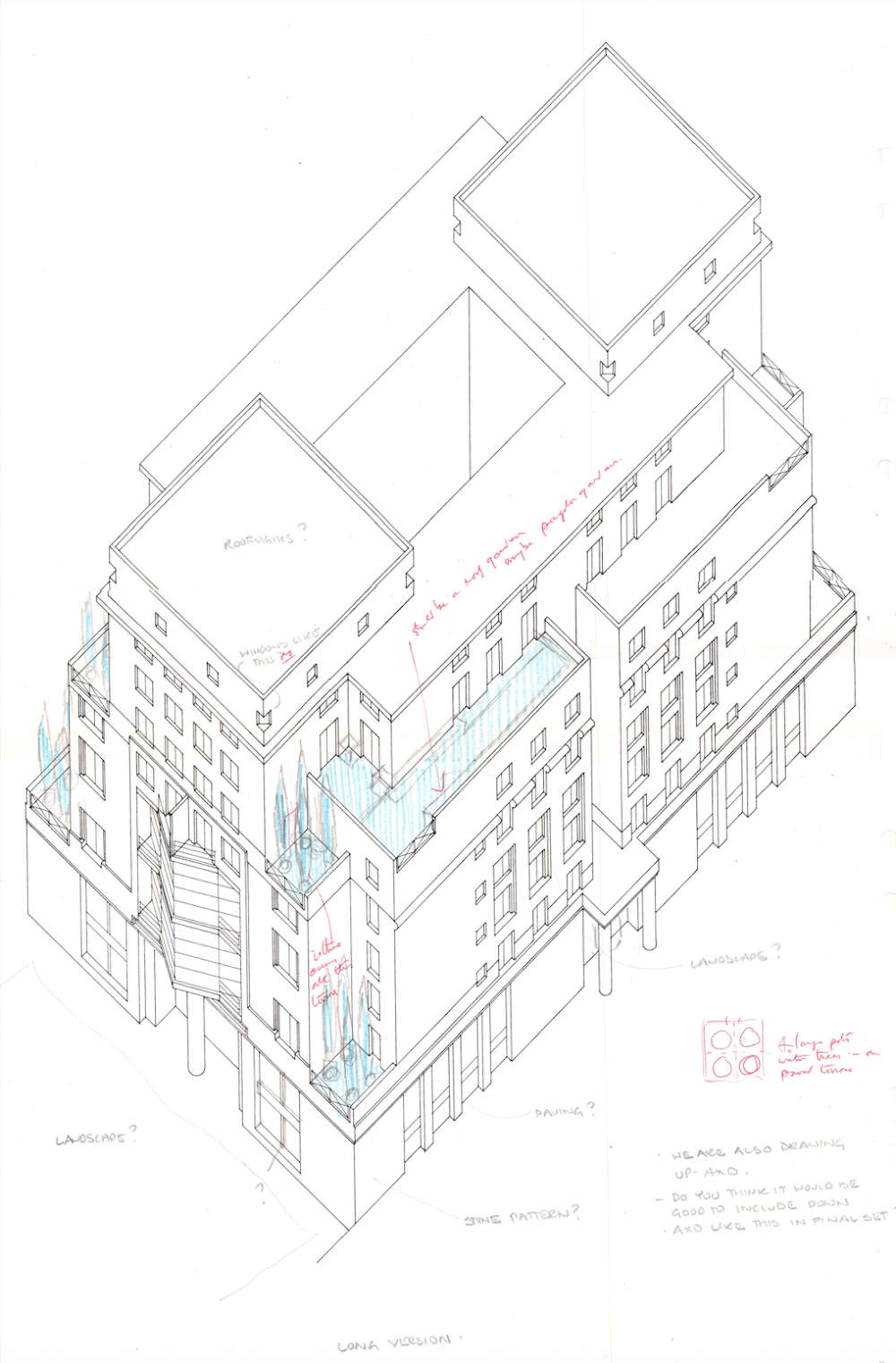

Stirling Wilford and Associates, Carlton Gardens axonometric with annotations in red by Stirling, 1988

One significant example of the perspective on the context was an invitational competition held in 1988 for the design in London of a building for offices and residences at Carlton Gardens, near Buckingham Palace. Historical research pointed to the particular features of the area: the plans of surrounding dwellings were analysed, as well as the bay windows, and the potential typological, proportional, and volumetric relationships with respect to the neighbouring constructions. The aim was to insert the architecture into the city, respecting the site and its essential characteristics. Some of the drawings produced on this occasion underline this logic, with project elevations and sections reaching a number of metres in length. When Stirling was asked by the planning office to explain the architectural choices made by the studio, he sent a detailed letter clearly illustrating his position and the relationship with context, function, and form. The work of architecture had to belong to the place containing it, interpreting it in a contemporary way, and it was made more original by the addition of design strategies unconstrained by the historical moment and the environment of the construction. Michael Wilford reflected on one of the strategies detached from the context: the habit of subdividing the building into a discrete number of parts, each of which was expressively approached separately and clearly. Robert Maxwell, a classmate of Stirling in Liverpool, observed that in certain projects we can see the rigour of a main axis of symmetry, while in others, the utilisation of a classical language occurred in ways that were far from classical. The most sophisticated aspect of Stirling’s repertoire is the ability to assemble elements distant in time into a coherent architectural whole, a particularity that was already reflected in his degree thesis and his collaboration with Gowan. Stirling recognised this ability in Hawksmoor and was fascinated. In the work of the studio, he enhanced it with more recent influences—himself mentioning Freud, Picasso, and Le Corbusier. This is a personal talent, hard to replicate, precisely like his sense of irony.

Excerpts from M. Iuliano, Stirling’s method, Casabella n. 964, December 2024, pp. 30-45.

Click here for Stirling’s readings at the University of Liverpool and here to access a summary of his profile.

Casabella 964/2024

2 Introduction

4-29 Timeline

30-45 Stirling’s method Marco Iuliano

46-58 Stirling's drawings Francesca Serrazanetti

58-111 In series and one-offs: twelve architectures, texts by Alicia A. Tymon-McEwan

112-117 James Stirling: two writings

118 -143 An anthology: R. Banham, N. Pevsner, M. Tafuri, J. Summerson, C. Rowe, K. Frampton, M. Wilford, L. Krier, P. Eisenman, A. Vidler, A. Reeser Lawrence, M. Crinson, C. Jencks, S. O’Donnell